J’Accuse…! Why Jeanne Calment’s 122-year old longevity record may be fake

(Note: To avoid work misattribution, please see the Authorship section at the end of this article)

For many gerontologists, Jeanne Calment is almost what Joan of Arc is for the French. A symbol, a legend, a saint. The longevity record of Jeanne of Arles, set at 122 years and 164 days, is known to every true aging fighter. Since Jeanne set it in 1997 nobody managed to break it or even get close — the second place barely exceeds 119 years, and the third stands at 117. Of those contenders who stand any chance — i.e. those who are presently alive — the oldest ones are just 115 years old. Given that after age 100 the annual probability of dying is about 1/2, the chances of a centenarian living to 122 are incredibly small.

But in gerontological circles nobody doubts the authenticity of Jeanne’s record. On the contrary, she is referred to as the “most validated centenarian”. Indeed, her documents are impeccable: she was born and lived her entire life in one place — the city of Arles in the south of France — and, coming from a well-known bourgeois family, Jeanne appears in many official sources. However, impeccable documents are no guarantee against fraud, as those documents could be used by someone else, someone younger. For example, your daughter.

Enter Yvonne

Jeanne did have a daughter. Yvonne Marie Nicolle Calment was born in 1898, when her mother was almost 23, and died, according to official documents, in 1934 on the day of her 36th birthday. Curiously, her death certificate was issued on the basis of testimony of a sole witness, a 71-year-old unemployed woman (i.e. not a doctor or nurse) who “saw her dead”:

And here’s the thing: in those rare photos of young Yvonne that survived — old Jeanne inexplicably ordered to burn all her family photos when the city of Arles asked her to provide them for the city’s archives — it is Yvonne who has the closest resemblance to the woman who lived to the year 1997. Moreover, the photo of young Yvonne had become widely known as a photo of Jeanne, labeled so in various sources, even ones as respectable as the prime authority on supercentenarians, Gerontology Research Group (from 2007 to 2018), or Wikipedia:

Let’s take a closer look at this photo. Here it is in decent resolution and colorized for your viewing pleasure by this algorithm:

Below is a close-up of the face from the original photo:

Does this photo really look like a photo of someone taken in Victorian 1897, when Jeanne was 22, as Wikipedia claims? Or does it seem more appropriate for the Flapper style of the “Roaring 1920s”? I am no expert, but an expert I respect — Alexander Vasiliev, the host of Russian TV show “Fashion Verdict” — believes the latter option much more likely:

“The dress is likely from around 1845, while the headpiece and hairstyle are 1930. Most likely the photo was taken in 1926–1930 in a vintage Arlesian Provence national costume.”

Interestingly, since 1903 Arles holds an annual national costume festival:

Maybe the photo in question is that of young Yvonne attending it. Given that in 1903 Jeanne would have been 28 and long married, I doubt that she would be participating, considering the nature of the festival:

“The Fête du Costume (Costume Festival) started in 1903, instigated by Frédéric Mistral (a famous French writer from the South of France) when he created the Festo Vierginenco (Festival of Virgins).

Young girls were invited to wear the dress and hair ribbon as a symbol of their passage into adulthood (up to the age of 15 they could only wear the “Mireille” costume).”

There is a curious aside related to the creator of the above festival, the champion of all things Occitan, Frédéric Mistral. When asked in one interview whether she had ever met him, Jeanne replied, “Yes! Yes, he was a friend of my father… um, he was a friend of my husband.” This wasn’t the only time when Jeanne seemed to confuse her husband and father in her recollections.

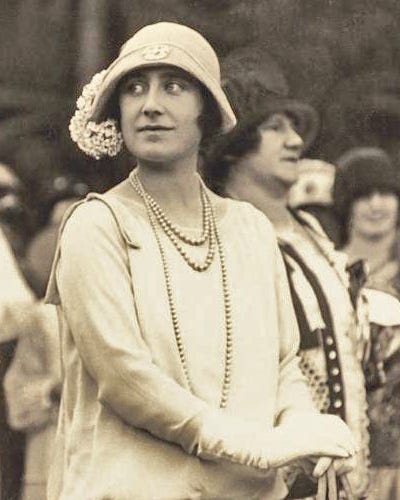

In any case, the hairstyle in the photo in question does look like those from the 1920s. Here is the Queen Mother, for example, in 1927:

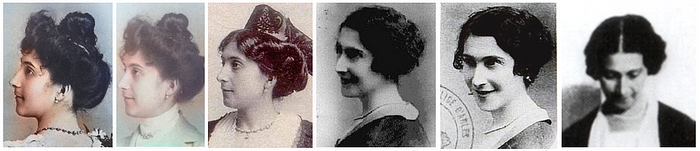

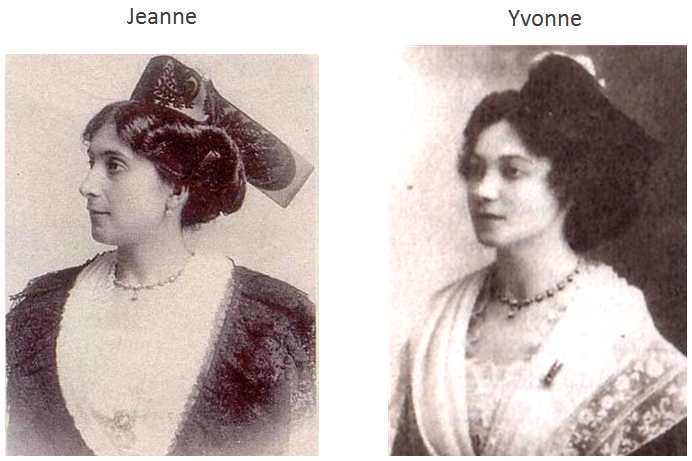

Finally, and this should settle the debate conclusively, in one of Jeanne’s biographies, the photo with a bow hat is signed as “Yvonne, daughter of Jeanne”, and above it is a photo of young Jeanne, which is more consistent with the Victorian spirit of the late XIX century:

A few more photos of young Jeanne have survived (colorized by me):

Here is Jeanne with her husband (Yvonne’s father):

The Smoking Gun?

Let us now look at mother and daughter in a more advanced age. Thankfully, one photo of them together had survived:

In my opinion, there can be no doubt that Yvonne is on the left and Jeanne on the right. Here are photos of Jeanne in chronological order:

I think that even the dress in the photos below is the same (the photo on the left is from Jeanne’s identification document):

But the “bow hat girl” is clearly Yvonne:

And if you compare the photos of young and adult Yvonne to the photos of the elderly and old Jeanne, the similarity is undeniable:

Spitting image:

By the way, is that a single earring in Yvonne’s right ear? What a rebel.

The Key Photo

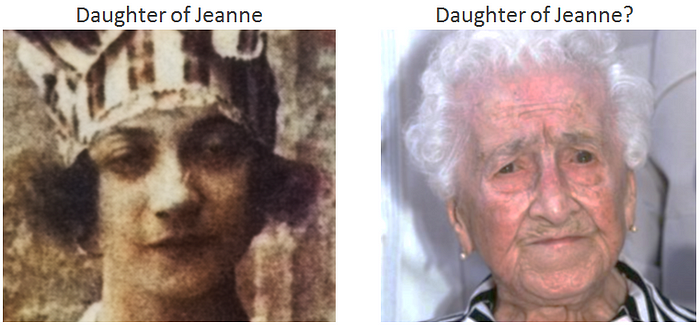

To my mind, the photo above holds the key to the mystery. Is this Jeanne or Yvonne? Just like in Highlander, there could be only one. If Yvonne really died in 1934, at age 36, there is no way she could have looked that old.

Let’s start our analysis from afar. Here are two interesting photos. One is of young Jeanne and the other one is of young Yvonne trying to recreate Jeanne’s photo. Apparently, Yvonne liked to mimic her mother from quite an early age:

We can see a clear difference in the chin and lower jaw. Yvonne also has a longer and thicker neck, with a more pronounced jugular notch. Here is a close-up:

Let’s now compare the photos of young Yvonne to the mystery photo. The chin, the lower jaw, the neck, the jugular notch are all similar:

The circled parts look outright identical:

Now, how about when compared to Jeanne?

To me the person in the middle has a wider, rounder face than Jeanne in the rightmost photo. Her neck is longer and wider, and her jugular notch is more pronounced. Her nose is also considerably bigger.

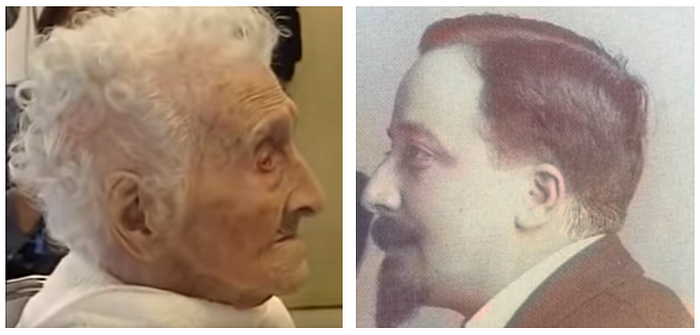

Below is an added photo of old “Jeanne” together with two confirmed photos of young Yvonne on the left:

When you see the four photos together, there is little doubt that the mystery photo is of the same person — Yvonne. I think it is pretty obvious:

By the way, the shape of the nose of the old woman is more like the shape of the nose of Yvonne’s father, rather than that of the young Jeanne:

Old Jeanne just doesn’t look like her young self — her nose, jaw, and chin are subtly different:

We have to concede, though, that Yvonne’s parents also look similar to each other, which is not surprising since they were second cousins.

The Motive

Why would Yvonne decide to impersonate her mother? One quite plausible motive is to avoid paying inheritance tax — in 1934 estate taxes reached as high as 38%. The family was quite wealthy, so paying sizable sums in estate taxes was probably still fresh in their minds, as Jeanne’s father passed away only a few years before, in 1931, and her mother in 1924.

In France, inheritance laws are quite peculiar even today, and they were considerably more so in the 1930s. Even inheritance between spouses was taxed; this rule was only abolished in 2007. Moreover, the surviving husband had the same rights to the property of his deceased wife (or even to her half of their joint property), as her children and even cousins! Therefore, if it were Jeanne who died in 1934, the financial impact on her family could have been quite severe — her husband would have to pay considerable tax on his large store. Moreover, he already did so just recently, as his own mother passed away in 1931, and she most likely was the original heiress to the store.

The scale of the Calment family shop can be appreciated from the photo below. It was no fruit stand. It was a large multistory building that Fernand Calment, Jeanne’s future husband, inherited from his parents, and which he managed from an early age — his father died in 1886, when Fernand was only 18 years old. He not only worked in this building, he also lived there with his mother. Jeanne moved in with them after the wedding.

Jeanne’s husband himself can be seen in front of his shop’s storefront in the 1907 photo (back row, in a light jacket, marked by the right arrow):

Here’s what a son of the longest-serving employee (marked by the second arrow in the photo above) had to say about the Calment store:

My poor father, Marius Maxence, who worked at this store for 7 years before World War I and 20 years after, was the oldest employee at the time of closing the store. After 27 years of faithful service (and a medal of labor), he was forced to change his profession.

…

The Calment store had a very large area between Antonefle Place, rue Gambetta, rue St Estève and rue Jean Granaud. The side of Rue Gambetta was reserved for selling fabrics of all kinds. With large shelves up to the ceiling and stairs to access the various shelves.

…

I remember in the 1930s I came to my father’s shop (I lived only a hundred meters from the bridge). I played with Frédy Billot, a grandson of Yvonne Calment and Colonel Billot. We had a difference of several months, and we hid behind jars or behind furniture.

…

The Calment family was well-known in Arles. You could even say that it was a bourgeois family who knew how to live, including Colonel Billot and his wife Yvonne Calment.

The line in bold caught my attention. Could a small boy remember how well Yvonne Calment “knew how to live” if she had officially died in 1934, when he was only 7 or 8 years old? Or maybe he and some other friends of the family knew that Yvonne didn’t die but took on her mother’s identity, and the line in bold is a sort of an “insider’s wink” to those in the know who remained alive in 1997 when this letter was written. It appeared in the local Arles Bulletin and it doesn’t look like it was written for outsiders.

Incidentally, it is interesting that Yvonne is absent from the 1931 census. Her parents are there, as well as her husband and son, everyone lives together, even the servants are mentioned, but Yvonne is not:

“A recopying error”, suggest authenticity validators of Jeanne’s longevity claims. Well, maybe. But could it be that real Jeanne was already dead by 1931? So maybe Yvonne passed herself for her mother to the census takers, in the process confusing them so much that they initially put her down under her grandmother’s name, Mary (see above)? And maybe 3 years later, Yvonne decided to officially legitimize her “death” and chose her birthday, January 19, as the date of death. This would be well in character for the naughty and daring lover of hunting and fencing. But let’s not venture too far into conjecture land, let’s just enumerate other inconsistencies.

Van Gogh

One of such inconsistencies has to do with Van Gogh, of whom old Jeanne had a very unflattering opinion, calling him ugly, rude, smelling of alcohol, and a “visitor of brothels”. Ostensibly, Jeanne met him in their family store in 1888 and even sold him, by various accounts, canvases, paints, or pencils. In some sources, the owner of the store is Jeanne’s father, while in others — her uncle. But Jeanne’s parents did not own a store; her father was a fourth-generation shipbuilder, and a very successful one at that. The Calment store was originally owned by Jeanne’s twice removed uncle (and the father of her future husband), but in 1888 — the year when Van Gogh came to Arles for a 15-month stay — the uncle had already been dead for 2 years.

In any case, I can hardly imagine a 13-year-old girl from a rich bourgeois family working behind the counter in 1888. I doubt that Jeanne or Yvonne worked a single day in their lives. By the way, according to the validators, at this age Jeanne was supposed to attend a Catholic boarding school (Benet private boarding school) — it would be interesting to confirm this fact in the school’s archive, and to also find out the students’ daily routine.

In another interview in 1989, Jeanne claimed that it was her husband who introduced her to Van Gogh. Apparently, Van Gogh came to the shop to buy canvases, and Jeanne’s husband told him: “Mr. Van Gogh, this is my wife!” Considering that in 1888 Jeanne was only 13 years old, this sounds quite odd. But her future husband (and Yvonne’s father) did, most likely, work at the store around that time. In 1888 he was 20 years old and it is quite logical to suppose that he took over the family business after his father’s death. Perhaps he sometimes told the story of meeting Van Gogh to his wife and daughter, and at some point Jeanne began to attribute this meeting to herself.

The Worst Insurance Deal Ever

It was in the very house where the Calment family store was located until 1937 that “Jeanne” used her apartment for the “worst insurance deal ever” in 1965 — pledging to transfer it upon her death to André-François Raffray in exchange for a lifetime monthly pension of 2500 francs. For the next 30 years Raffray paid out more than twice the value of the apartment and did not even get to enjoy it, as he succumbed to cancer before Jeanne’s death. Payments to Jeanne, however, continued.

Amazingly, this case is described in Jean-Pierre Daniel’s book Insurance and Its Secrets as a scam known in the narrow circles of insurers. Here is what he writes:

Everyone remembers that Jeanne Calment officially died at the age of 122, on August 4, 1997. At that time, it was said that this lady had a life annuity, and this is true. This annuity was paid by a large French company, which wasn’t very pleased with such exceptional longevity. Moreover, the company was well aware that it is paying not Jeanne Calment, but her daughter. In fact, after the death of the true Jeanne Calment, her daughter, who at that time was herself far from a child, took the identity of her mother in order to continue receiving payments. The insurance company has discovered identity theft, but with consent from — or on at the request of? — the authorities did not make it public because the “elder of the French” became a legend.

The “took the identity of her mother in order to continue receiving payments” part is clearly a mistake, since Jeanne made this deal only in 1965, 31 years after the death of her daughter/mother. It is also not entirely clear how Raffray’s annuity obligation got transferred to an insurance company, although it is quite possible that he decided to hedge his risks and bought a special longevity insurance policy on Jeanne’s life — one which paid out monthly installments until her death.

Curiouser and curiouser

Another interesting circumstance is that after Yvonne’s death in 1934, her husband, who was 43 at that time, never remarried, but continued living together with his “mother-in-law” until his death. Initially, according to census data, Yvonne’s husband and their son Frederic lived in an apartment adjacent to that of Jeanne and her husband (who died in 1942), but after Frederic got married, Yvonne’s widower moved in with Jeanne where he stayed until his death in 1963. This certainly doesn’t prove anything, but it is what one would expect if Yvonne truly did not die and simply began to impersonate her mother.

In 1942, Jeanne’s husband (Yvonne’s father) died from cherry poisoning. In early 1963 Jeanne’s son-in-law (Yvonne’s husband) died, and her grandson Frederic died in a car accident a few months after. After that, Jeanne led a rather quiet if not reclusive life. Even on her 100th birthday, she refused the offer of the Arles mayor to arrange for a public celebration of this very rare occasion. The mayor recalled some very curious details:

“When I learned that someone from Arles turns 100 years old,” Jacques said, “by tradition, I had to go to her house, inviting her family and bringing a gift. I was refused, politely, but firmly. Mme. Calment wanted no ceremony: no drums, no trumpets, no presents, no cake. She was assured that no one would know about her centennial. Only then did Jeanne agreed to come to the city hall herself. I waited for Jeanne for a long time in the reception area until it became clear that one of the sitting women, who hardly looked eighty, was the hero of the day.

Jeanne’s uncanny good physical condition also amazed many professional gerontologists who investigated her phenomenon. Particularly surprising was her ability to stand and walk under her own power at the age of 113:

Moreover, at 114 years old, her height was 150 cm, which is only 2 cm less than her stated height in adulthood:

Considering that usually after age 40 our height begins to decline and, on average, by age 80 women experience a 6 cm decrease, such height preservation in Jeanne’s case is quite unprecedented:

Interestingly, Yvonne seems to have been taller than Jeanne:

By the way, on Jeanne’s ID card above, the color of her eyes is listed as “black,” although old Jeanne’s color is clearly different:

Finally, at age 118, for a 6-month period Jeanne has been undergoing various cognitive tests, in which she showed results comparable to those of 80–90-year-olds.

At times, Jeanne’s inconsistencies could be quite telling. She would sometimes refer to her husband as “my father”, or say that her mother’s last name “Gilles” comes from her grandmother, although Jeanne did not have a grandmother with such last name. One of the most revealing things Jeanne said was that as a child she was taken to school by their maid, Marthe Fousson. However, according to a 1911 census, Marthe Fousson was 10 years younger than Jeanne, so the only person she could have accompanied to school was Yvonne, with whom she lived according to the same census.

Of course, each particular incorrect memory or biographical discrepancy could be a coincidence. But taken together, their collective weight is quite compelling to try to find answers to some of these questions, and dig a little deeper into the biography of this intriguing woman. Hopefully, the international gerontological community would support this idea rather than consider it a sacrilege.

In conclusion, a kind request: if you come across any new evidence for or against any claims expressed here, please share it. You can do so in the comments or via PM.

PS: There is now an online petition to extract Jeanne’s and Yvonne’s DNAfrom their remains to conclusively establish whether the identity switch hypothesis is true or false.

More evidence has come to light recently. For example, old and young Jeanne’s ears are different. I’ve written a full update here.

Read part 3 of my Jeanne Calment series here.

Authorship: This article was inspired by the research of Nikolai Zak (see preprint here), who was asked to look into Jeanne Calment by Valerii Novoselov. I have analyzed the evidence published by Nikolai and used those facts that I considered credible and relevant in my story above. However, parts of this article are based on my own thoughts, in particular:

- Period fashion analysis of the bow hat photo which rules out that the photo was taken in the XIX century thereby strengthening the case that is a photo of Yvonne rather than Jeanne

- Background information on Arlesian Costume Festival as a potential occasion to which Yvonne could have worn the outfit in the bow hat photo

- Old Jeanne/Yvonne mystery photo analysis highlighting common features between young Yvonne and the person in the photo: chin, jugular notch, etc. which strengthens the case that it was Yvonne who lived to old age rather than Jeanne (as only one of them could)

- The hypothesis that it was Jeanne’s husband’s family store that was the primary object of potential tax evasion based on the fact that common family property was also subject to inheritance tax

For those who are interested in delving deeper into this topic, I recommend getting acquainted with the primary sources from Nikolai (article in Russian, slides in Russian), as well as reading the English-language interview on this topic with Valerii.

Update: Here is a detailed overview of how I became interested in Jeanne’s story, what my role was in the investigation and what were my research contributions: